Addison's disease

| Addison's disease | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | E27.1-E27.2 |

| ICD-9 | 255.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 222 |

| MedlinePlus | 000378 |

| eMedicine | med/42 |

| MeSH | D000224 |

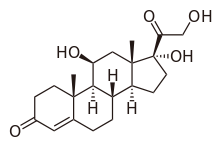

Addison’s disease (also Addison disease, chronic adrenal insufficiency,hypocortisolism, and hypoadrenalism) is a rare, chronic endocrine system disorder in which the adrenal glands do not produce sufficient steroid hormones (glucocorticoids and often mineralocorticoids). It is characterised by a number of relatively nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain and weakness, but under certain circumstances, these may progress to Addisonian crisis, a severe illness which may include very low blood pressure and coma.

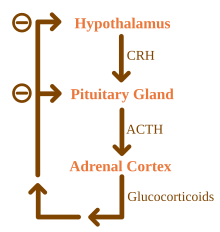

The condition arises from problems with the adrenal gland, primary adrenal insufficiency, and can be caused by damage by the body's own immune system, certain infections, or various rarer causes. Addison's disease is also known as chronic primary adrenocortical insufficiency, to distinguish it from acute primary adrenocortical insufficiency, most often caused by Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome. Addison's disease should also be distinguished from secondary and tertiary adrenal insufficiency, which are caused by deficiency of ACTH (produced by the pituitary gland) and CRH(produced by the hypothalamus), respectively. Despite this distinction, Addisonian crises can happen in all forms of adrenal insufficiency.

Addison's disease and other forms of hypoadrenalism are generally diagnosed via blood tests and medical imaging.[1] Treatment involves replacing the absent hormones (oral hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone).[2] Lifelong, continuous steroid replacement therapy is required, with regular follow-up treatment and monitoring for other health problems.[1]

Addison’s disease is named after Thomas Addison, a graduate of the University of Edinburgh Medical School who first described the condition in 1849. The adjective "Addisonian" is used to describe features of the condition, as well as patients suffering from Addison’s disease.[1]

Contents

[show]Signs and symptoms[edit]

The symptoms of Addison's disease develop insidiously and may take time to be recognised. The most common symptoms are fatigue, lightheadedness upon standing or while upright, muscle weakness, fever, weight loss, difficulty in standing up, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea,headache, sweating, changes in mood and personality, and joint and muscle pains. Some have marked cravings for salt or salty foods due to the urinary losses of sodium.[1] Hyperpigmentationof the skin may be noted, particularly in sun-exposed areas, as well as darkening of the palmar creases, sites of friction, recent scars, the vermilion border of the lips, and genital skin.[3] This is not encountered in secondary and tertiary hypoadrenalism.[2]

Clinical signs

On physical examination, the following may be noticed:[1]

- Low blood pressure that falls further when standing (orthostatic hypotension)

- Most people with primary Addison's have darkening (hyperpigmentation) of the skin, including areas not exposed to the sun; characteristic sites are skin creases (e.g. of the hands), nipple, and the inside of the cheek (buccal mucosa); also, old scars may darken. This occurs because melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) share the same precursor molecule, pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). After production in theanterior pituitary gland, POMC gets cleaved into gamma-MSH, ACTH and beta-lipotropin. The subunit ACTH undergoes further cleavage to produce alpha-MSH, the most important MSH for skin pigmentation. In secondary and tertiary forms of Addison's, skin darkening does not occur.

- Medical conditions, such as type I diabetes, thyroid disease (Hashimoto's thyroiditis andgoiter), and vitiligo often occur together with Addison's (often in the setting of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome). Hence, symptoms and signs of any of the former conditions may also be present in the individual with Addison's. The occurrence of Addison's disease in someone who also has Hashimoto's thyroiditis is called Schmidt syndrome.

Addisonian crisis

Main article: Adrenal crisis

An "Addisonian crisis" or "adrenal crisis" is a constellation of symptoms that indicates severe adrenal insufficiency. This may be the result of either previously undiagnosed Addison's disease, a disease process suddenly affecting adrenal function (such as adrenal hemorrhage), or an intercurrent problem (e.g. infection, trauma) in someone known to have Addison's disease. It is a medical emergency and potentially life-threatening situation requiring immediate emergency treatment.

Characteristic symptoms are:[4]

- Sudden penetrating pain in the legs, lower back or abdomen

- Severe vomiting and diarrhea, resulting in dehydration

- Low blood pressure

- Syncope (loss of consciousness and ability to stand)

- Hypoglycemia (reduced level of blood glucose)

- Confusion, psychosis, slurred speech

- Severe lethargy

- Hyponatremia (low sodium level in the blood)

- Hyperkalemia (elevated potassium level in the blood)

- Hypercalcemia (elevated calcium level in the blood)

- Convulsions

- Fever

Causes

Causes of adrenal insufficiency can be categorized by the mechanism through which they cause the adrenal glands to produce insufficient cortisol. These are adrenal dysgenesis (the gland has not formed adequately during development), impaired steroidogenesis (the gland is present but is biochemically unable to produce cortisol) or adrenal destruction (disease processes leading to glandular damage).[1]

Adrenal dysgenesis

All causes in this category are genetic, and generally very rare. These include mutations to the SF1 transcription factor, congenital adrenal hypoplasia (CAH) due to DAX-1 gene mutations and mutations to the ACTH receptor gene (or related genes, such as in the Triple A or Allgrove syndrome). DAX-1 mutations may cluster in a syndrome with glycerol kinase deficiency with a number of other symptoms when DAX-1 is deleted together with a number of other genes.[1]

Impaired steroidogenesis

To form cortisol, the adrenal gland requires cholesterol, which is then converted biochemically into steroid hormones. Interruptions in the delivery of cholesterol include Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and abetalipoproteinemia.

Of the synthesis problems, congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the most common (in various forms: 21-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, 11β-hydroxylase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), lipoid CAH due to deficiency of StAR and mitochondrial DNA mutations.[1] Some medications interfere with steroid synthesis enzymes (e.g. ketoconazole), while others accelerate the normal breakdown of hormones by the liver (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin).[1]

Adrenal destruction

Autoimmune adrenalitis is the most common cause of Addison's disease in the industrialised world. Autoimmune destruction of theadrenal cortex is caused by an immune reaction against the enzyme 21-hydroxylase (a phenomenon first described in 1992).[5] This may be isolated or in the context of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS type 1 or 2), in which other hormone-producing organs, such as the thyroid and pancreas, may also be affected.[6]

Adrenal destruction is also a feature of adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), and when the adrenal glands are involved in metastasis (seeding ofcancer cells from elsewhere in the body, especially lung), hemorrhage (e.g. in Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome or antiphospholipid syndrome), particular infections (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), or the deposition of abnormal protein in amyloidosis.[7]

Corticosteroid withdrawal

Use of high-dose steroids for more than a week begins to produce suppression of the patient's adrenal glands because the exogenous glucocorticoids suppress hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). With prolonged suppression, the adrenal glands atrophy (physically shrink), and can take months to recover full function after discontinuation of the exogenous glucocorticoid. During this recovery time, the patient is vulnerable to adrenal insufficiency during times of stress, such as illness.[8]

Diagnosis

Suggestive features

Routine laboratory investigations may show the following:[1]

- Hypercalcemia

- Hypoglycemia, low blood sugar (worse in children due to loss of glucocorticoid's glucogenic effects)

- Hyponatremia (low blood sodium levels), due to the kidney's inability to excrete free water in the absence of sufficient cortisol, and also the effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone to stimulate secretion of ADH. That hyponatremia occurs even in secondary adrenal insufficiency (i.e. due to pituitary disease), in which aldosterone deficiency is not a feature, underscores the fact that hyponatremia in Addison's disease is not due to lack of aldosterone.

- Hyperkalemia (raised blood potassium levels), due to loss of production of the hormone aldosterone.

- Eosinophilia and lymphocytosis (increased number of eosinophils or lymphocytes, two types of white blood cells)

- Metabolic acidosis (increased blood acidity), also is due to loss of the hormone aldosterone because sodium reabsorption in the distal tubule is linked with acid/hydrogen ion (H+) secretion. Low levels of aldosterone stimulation of the renal distal tubule leads to sodium wasting in the urine and H+ retention in the serum.

Testing

In suspected cases of Addison's disease, demonstration of low adrenal hormone levels even after appropriate stimulation (called the ACTH stimulation test) with synthetic pituitary ACTH hormonetetracosactide is needed for the diagnosis. Two tests are performed, the short and the long test. It should be noted that dexamethasone does not cross-react with the assay and can be administered concomitantly during testing.

The short test compares blood cortisol levels before and after 250 micrograms of tetracosactide (intramuscular or intravenous) is given. If, one hour later, plasma cortisol exceeds 170 nmol/l and has risen by at least 330 nmol/l to at least 690 nmol/l, adrenal failure is excluded. If the short test is abnormal, the long test is used to differentiate between primary adrenal insufficiency and secondary adrenocortical insufficiency.

The long test uses 1 mg tetracosactide (intramuscular). Blood is taken 1, 4, 8, and 24 hr later. Normal plasma cortisol level should reach 1000 nmol/l by 4 hr. In primary Addison's disease, the cortisol level is reduced at all stages, whereas in secondary corticoadrenal insufficiency, a delayed but normal response is seen.

Other tests may be performed to distinguish between various causes of hypoadrenalism, including renin and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, as well as medical imaging - usually in the form of ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.

Adrenoleukodystrophy, and the milder form, adrenomyeloneuropathy, cause adrenal insufficiency combined with neurological symptoms. These diseases are estimated to be the cause of adrenal insufficiency in about 35% of male patients with idiopathic Addison’s disease, and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any male with adrenal insufficiency. Diagnosis is made by a blood test to detect very long chain fatty acids.[9]

Treatment

Maintenance

Treatment for Addison's disease involves replacing the missing cortisol, sometimes in the form of hydrocortisone tablets, or prednisonetablets in a dosing regimen that mimics the physiological concentrations of cortisol. Alternatively, one-quarter as much prednisolone may be used for equal glucocorticoid effect as hydrocortisone. Treatment is usually lifelong. In addition, many patients require fludrocortisoneas replacement for the missing aldosterone. Caution must be exercised when persons with Addison's disease become unwell withinfection, have surgery or other trauma, or become pregnant. In such instances, their replacement glucocorticoids, whether in the form of hydrocortisone, prednisone, prednisolone, or other equivalent, often must be increased. Inability to take oral medication may prompt hospital admission to receive steroids intravenously. People with Addison's are often advised to carry information on them (e.g., in the form of a MedicAlert bracelet) for the attention of emergency medical services personnel who might need to attend to their needs.

Crisis

Standard therapy involves intravenous injections of glucocorticoids and large volumes of intravenous saline solution with dextrose (glucose). This treatment usually brings rapid improvement. When the patient can take fluids and medications by mouth, the amount of glucocorticoids is decreased until a maintenance dose is reached. If aldosterone is deficient, maintenance therapy also includes oral doses of fludrocortisone acetate.[10]

Epidemiology

The frequency rate of Addison's disease in the human population is sometimes estimated at roughly one in 100,000.[11] Some research and information sites put the number closer to 40-60 cases per million population. (1/25,000-1/16,600)[12] (Determining accurate numbers for Addison's is problematic at best and some incidence figures are thought to be underestimates.[13]) Addison's can afflict persons of any age, gender, or ethnicity, but it typically presents in adults between 30 and 50 years of age.[14] Research has shown no significant predispositions based on ethnicity.[12]

Prognosis

With proper medication, especially hormone replacement therapy, patients can expect to live relatively normal lives.[15]

People with adrenal insufficiency should always carry identification stating their condition in case of an emergency. The card should alert emergency personnel about the need to inject 100 mg of cortisol if its bearer is found severely injured or unable to answer questions. The card should also include the doctor's name and telephone number and the name and telephone number of the nearest relative to be notified.[16]

When traveling, a needle, syringe, and an injectable form of cortisol should be carried for emergencies. A person with Addison's disease also should know how to increase medication during periods of stress or mild upper respiratory infections. Immediate medical attention is needed when severe infections, vomiting, or diarrhea occurs, as these conditions can precipitate an Addisonian crisis. A patient who is vomiting may require injections of hydrocortisone, since oral hydrocortisone supplements cannot be adequately metabolized.[17]

History

Discovery and development

Addison’s disease is named after Thomas Addison, the British physician who first described the condition in 'On the Constitutional and Local Effects of Disease of the Suprarenal Capsules (1855).[18] All of Addison's six original patients had tuberculosis of the adrenal glands.[19] While Addison's six patients in 1855 all had adrenal tuberculosis, the term "Addison's disease" does not imply an underlying disease process.

The condition was initially considered a form of anemia associated with the adrenal glands. Because little was known at the time about the adrenal glands (then called "Supra-Renal Capsules"), Addison’s monograph describing the condition was an isolated insight. As the adrenal function became better known, Addison’s monograph became known as an important medical contribution and a classic example of careful medical observation.[20]

Notable cases

- United States President John F. Kennedy was one of the best-known Addison's disease sufferers. He was possibly one of the first Addisonians to survive major surgery.[21]Substantial secrecy surrounded his health during his years as president.[22]

- Eunice Kennedy Shriver, one of John F. Kennedy's sisters, was believed to have Addison's disease as well.[23]

- Popular singer Helen Reddy[24]

- Scientist Eugene Merle Shoemaker, co-discoverer of the Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.[25]

- French Carmelite nun and religious writer Blessed Elizabeth of the Trinity[26]

- American artist Ferdinand Louis Schlemmer died from Addison's disease.

- Some have suggested Jane Austen was an avant la lettre case, but others have disputed this.[27]

- According to Carl Abbott, a Canadian medical researcher, Charles Dickens may also have been affected.[28]

- Australia's youngest rugby league football international, Geoff Starling[29]

- Osama bin Laden may have been an Addisonian. Lawrence Wright noted that bin Laden manifested all the key symptoms, such as "low blood pressure, weight loss, muscle fatigue, stomach irritability, sharp back pains, dehydration, and an abnormal craving for salt". Bin Laden was known to have consumed large amounts of the drug sulbutiamine to treat his symptoms.[30]

- Basque nationalist and founder of the Basque Nationalist Party, Sabino Arana died in Sukarrieta at the age of 38 after falling ill with Addison's disease during time spent in prison.

- One of Canada's top gymnasts, Nathan Gafuik, was diagnosed with Addison's disease when he was 15.[31]

Other animals

Main article: Addison's disease in canines

The condition has been diagnosed in all breeds of dogs. In general, it is underdiagnosed, and one must clinically suspect it as an underlying disorder for many presenting complaints. Females are overrepresented, and the disease often appears in middle age (4–7 yr), although any age or either gender may be affected. Genetic continuity between dogs and humans helps to explain the occurrence of Addison's disease in both species.[32]

Hypoadrenocorticism is treated with fludrocortisone or a monthly injection called Percorten V (desoxycorticosterone pivlate (DOCP)) and prednisone. Routine blood work is necessary in the initial stages until a maintenance dose is established. Most of the medications used in the therapy of hypoadrenocorticism cause excessive thirst and urination, making it important to provide enough drinking water. If the owner knows about an upcoming stressful situation (shows, traveling, etc.), patients generally need an increased dose of prednisone to help deal with the added stress. Avoidance of stress is important for dogs with hypoadrenocorticism.

No comments:

Post a Comment