Cerebral hemorrhage

| Cerebral hemorrhage | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Cerebral hemorrhage

| |

A cerebral haemorrhage (also spelled hemorrhage; aka intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral hematoma, intracranial hematoma) is a subtype of intracranial hemorrhage that occurs within the brain tissue itself. It is alternatively called intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). It can be caused by brain trauma, or it can occur spontaneously in hemorrhagic stroke. Non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage is a spontaneous bleeding into the brain tissue.[1]

A cerebral hemorrhage is an intra-axial hemorrhage; that is, it occurs within the brain tissue rather than outside of it. The other category of intracranial hemorrhage is extra-axial hemorrhage, such as epidural, subdural, and subarachnoid hematomas, which all occur within the skull but outside of the brain tissue. There are two main kinds of intra-axial hemorrhages: intraparenchymal hemorrhage and intraventricular hemorrhages. As with other types of hemorrhages within the skull, intraparenchymal bleeds are a serious medical emergency because they can increase intracranial pressure, which if left untreated can lead to coma and death. Themortality rate for intraparenchymal bleeds is over 40%.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Patients with intraparenchymal bleeds have symptoms that correspond to the functions controlled by the area of the brain that is damaged by the bleed.[3] Other symptoms include those that indicate a rise in intracranial pressure caused by a large mass putting pressure on the brain.[3] Intracerebral hemorrhages are often misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhages due to the similarity in symptoms and signs. A severe headache followed by vomiting is one of the more common symptoms of intracerebral hemorrhage. Some patients may also go into a coma before the bleed is noticed.

Causes

Intracerebral bleeds are the second most common cause of stroke, accounting for 10% of hospital admissions for stroke.[4] High blood pressure raises the risks of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage by two to six times.[1] More common in adults than in children, intraparenchymal bleeds are usually due to penetrating head trauma, but can also be due to depressed skull fractures. Acceleration-deceleration trauma,[5][6][7] rupture of an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM), and bleeding within a tumor are additional causes. Amyloid angiopathy is a not uncommon cause of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients over the age of 55. A very small proportion is due to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Infection with the k serotype of Streptococcus mutans may also be a risk factor, because of its prevalence in stroke patients and production of collagen-binding protein.[8]

Risk factors for ICH include:[9]

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Menopause

- Cigarette smoking

- Excessive alcohol consumption

Tramautic intracerebral hematomas are divided into acute and delayed. Acute intracerebral hematomas occur at the time of the injury while delayed intracerebral hematomas have been reported from as early as 6 hours post injury to as long as several weeks.

Diagnosis

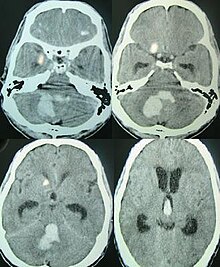

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage can be recognized on CT scans because blood appears brighter than other tissue and is separated from the inner table of the skull by brain tissue. The tissue surrounding a bleed is often less dense than the rest of the brain because of edema, and therefore shows up darker on the CT scan. Frequently, a CT angiogram will be performed in order to exclude a secondary cause of hemorrhage[10] or to detect a "spot sign".[11]

Treatment

Treatment depends substantially of the type of ICH. Rapid CT scan and other diagnostic measures are used to determine proper treatment, which may include both medication and surgery.

Medication

- Antihypertensive therapy in acute phases. The AHA/ASA and EUSI guidelines (American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines and the European Stroke Initiative guidelines) have recommended antihypertensive therapy to stabilize the mean arterial pressure at 110 mmHg. One paper showed the efficacy of this antihypertensive therapy without worsening outcome in patients of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage within 3 hours onset.[12]

- Giving Factor VIIa within 4 hours limits the bleeding and formation of a hematoma. However, it also increases the risk ofthromboembolism.[13]

- Mannitol is effective in acutely reducing raised intracranial pressure.

- Acetaminophen may be needed to avoid hyperthermia, and to relieve headache.[13]

- Frozen plasma, vitamin K, protamine, or platelet transfusions are given in case of a coagulopathy.[13]

- Fosphenytoin or other anticonvulsant is given in case of seizures or lobar hemorrhage.[13]

- H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors are commonly given for stress ulcer prophylaxis, a condition somehow linked with ICH.[13]

- Corticosteroids, were thought to reduce swelling. However, in large controlled studies, corticosteroids haven been found to increase mortality rates and are no longer recommended.[14][15]

Surgery

Surgery is required if the hematoma is greater than 3 cm (1 in), if there is a structural vascular lesion or lobar hemorrhage in a young patient.[13]

- A catheter may be passed into the brain vasculature to close off or dilate blood vessels, avoiding invasive surgical procedures.[16]

- Aspiration by stereotactic surgery or endoscopic drainage may be used in basal ganglia hemorrhages, although successful reports are limited.[13]

Other treatment

- Tracheal intubation is indicated in patients with decreased level of consciousness or other risk of airway obstruction.[13]

- IV fluids are given to maintain fluid balance, using isotonic rather than hypotonic fluids.[13]

Prognosis

The risk of death from an intraparenchymal bleed in traumatic brain injury is especially high when the injury occurs in the brain stem.[2] Intraparenchymal bleeds within the medulla oblongata are almost always fatal, because they cause damage to cranial nerve X, the vagus nerve, which plays an important role in blood circulation and breathing.[5] This kind of hemorrhage can also occur in the cortex or subcortical areas, usually in the frontal or temporal lobes when due to head injury, and sometimes in the cerebellum.[5][17]

For spontaneous ICH seen on CT scan, the death rate (mortality) is 34–50% by 30 days after the insult,[1] and half of the deaths occur in the first 2 days.[18] Even though the majority of deaths occurs in the first days after ICH, survivors have a long term excess mortality of 27% compared to the general population.[19]

The inflammatory response triggered by stroke has been viewed as harmful in the early stage, focusing on blood-borne leukocytes, neutrophils and macrophages, and resident microglia and astrocytes.[20] A human postmortem study shows that inflammation occurs early and persists for several days after ICH.[21] New area of interest are the Mast Cells.[22]

Epidemiology

It accounts for 20% of all cases of cerebrovascular disease in the US, behind cerebral thrombosis (40%) and cerebral embolism (30%).[23]

In 1945, U.S President Franklin D. Roosevelt died from a cerebral hemorrhage.

No comments:

Post a Comment